BAG-ONG TUIG NA, ug isip akong unang tampo dinhi sa BESO BISDAK karong 2006, tugoti nga molingi ko'g balik pinaagi 'ning lakbit-saysay kabahin sa akong panuwat sa pinulongang Bisaya. Pwera buyag, ania'y lindog ni Jose R. Reyes nga napatik sa Sun.Star Weekend Magazine (Pebrero 7, 1999):

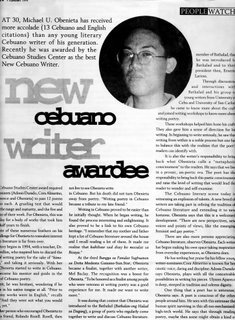

At 30, Michael U. Obenieta has received more accolades (13 Cebuano and English citations) than any young literary writer of his generation. Recently, the Cebuano Studies Center of the University of San Carlos (and the Cornelio Faigao Foundation) cited him as the first recipient of the “Best New Cebuano Writer” award.

At 30, Michael U. Obenieta has received more accolades (13 Cebuano and English citations) than any young literary writer of his generation. Recently, the Cebuano Studies Center of the University of San Carlos (and the Cornelio Faigao Foundation) cited him as the first recipient of the “Best New Cebuano Writer” award.

The award required the four nominees (Adonis Durado, Cora Almerino, Ulysses Aparece, and Obenieta) to pass 12 poems in Cebuano each. A grueling test that would determine the range and maturity, "the fire and performance of their work," as Dr. Resil Mojares affirmed when he served as one of the judges along with Prof. Merlie Alunan and Rene Amper. For Obenieta, this was judgment day for a body of work that took him one and a half year to finish. In spite of the numerous feathers on his cap, the challenge for Obenieta to reawaken interest in Cebuano literature is far from over.

His story begins in 1994 with a teacher, Dr. Romola Savellon, (his Literature professor in the erstwhile Cebu State College) who inspired him to discard the trappings of writing poetry for the sake of “himo-himo lang,” and to take it seriously. Savellon became his mentor and guide in the rudiments of poetry.

At first, he was hesitant, wondering if he could write in his native tongue at all. “Prior to 1994, all my works were in English,” recalls Obenieta. “And they were not what you call poetry, yet.” Another one who encouraged Obenieta to write was his friend Rolando Rosell. A novelist in Cebuano, Rosell, then Obenieta’s editor at the college publication “Ang Suga,” would not live to see Obenieta write in Cebuano. “Writing poetry in Cebuano became a tribute of sorts to my late friend.” Writing in Cebuano proved to be easier than he initially thought.

When he started writing, he found the process interesting and enlightening. It also proved to be a link to his own Cebuano heritage. “I remember that my parents kept some Cebuano literature (Bisaya and Lungsoranon, particularly) in the house, and I recall reading a lot of these. It made me realize, kahibaw sad dai’y ko mosulat og Binisaya.”

At the third Bangga sa Panulat Sugbuanon (co-sponsored by the Doña Modesta Gaisano Foundation and Sun.Star Cebu), Obenieta became the youngest finalist (in a field that included his writing idol at that time, Mel Baclay). The recognition was a boost for Obenieta. “To be honored as a finalist among people who were veterans in writing poetry… made me want to write more.”

It was during the awarding ceremony when Obenieta was introduced to the Bathalad (Bathalan-ong Halad sa Dagang), a group of creative writers who regularly come together to write and discuss Cebuano literature. It was Baclay, a Bathalad member, who introduced Obenieta to the group’s president then, Ernesto Lariosa. Through discussions and interactions with Bathalad and his own group of young writers from the University of Cebu and the University of San Carlos, he came to know more about the craft.

He was accepted to the country’s writing workshops (Dumaguete, Baguio, Iligan, among others.) These workshops helped him hone his craft, giving him a sense of direction for his writing. In beginning to write seriously, he saw that writing from within is a noble process but one has to balance this with the realities that the readers can identify with. It is also the writer’s responsibility to bring back a “metaphoric consciousness” to the readers.

He says that we live in a prosaic, un-poetic times. The poet has the responsibility to bring back this poetic consciousness and raise the level of writing that would lead the reader to wonder and self-examination. The Cebuano literary scene today is witnessing an explosion of talents. A new breed of writers are taking part in reliving the Cebuano tradition and  extending it to new horizons in writing. “There are new perspectives, new voices voices and points of views, like the emerging feminist and gay poetry.” There are also more people appreciating Cebuano literature, observes Obenieta. Each writer has begun making his own creative space and taking inspiration from everyday experiences, as Obenieta does. He has nothing but praise for his fellow young writers-nominees. Cora Almerino is known for her caustic voice, daring and discipline. Adonis Durado, says Obenieta, plays with all the conceivable possibilities in poetry. Ulysses Aparece is steeped in tradition.

extending it to new horizons in writing. “There are new perspectives, new voices voices and points of views, like the emerging feminist and gay poetry.” There are also more people appreciating Cebuano literature, observes Obenieta. Each writer has begun making his own creative space and taking inspiration from everyday experiences, as Obenieta does. He has nothing but praise for his fellow young writers-nominees. Cora Almerino is known for her caustic voice, daring and discipline. Adonis Durado, says Obenieta, plays with all the conceivable possibilities in poetry. Ulysses Aparece is steeped in tradition.

A poet possesses an antennae, Obenieta says. A poet is conscious of the world around him. With this antennae, he sees the human spirit surviving against this mechanical, high-tech world. By writing and reading poetry, he says, maybe some might obtain sort of a state of grace.