the Evolution of the Cebuano Poetic Tradition

(A paper presented at the National Conference for Young Writers and the Literary Traditions at Bohol Tropics, Tagbilaran City, 27-30 January 2000, sponsored by the National Commission for the Culture and the Arts (NCCA). Later printed in the anthology Write-Hop: New Writers Speak published by the NCCA.)

The Irish Connection

Something about the literature of Ireland makes me wish to be reincarnated as an Irish in my next lifetime. There’s this sense of co-existing with the written Irish lives which, I must clarify, is not as trenchant as when I get vicarious with the other literatures which I can savor only at a certain remove. The human condition is universal, I know, but the realm of reality rendered to me by Irish authors is something I can view from my window.

Blame it on the Irish coffee I was sipping, I suppose. There’s a certain epiphany in the experience of reading James Joyce, Christy Brown or the brothers McCourt that gives me an eerie feeling of living within the book’s covers, where the temperament of the characters and the characteristics of the milieu sort of cue in an extension of my own existence.I can swear that Jim Sheridan’s critically-acclaimed film, My Left Foot— one of my all-time favorites— featured characters from my own neighborhood. And I need not be afflicted with cerebral palsy to know that. I haven’t seen Angela’s Ashes yet, but I have this sneaking suspicion that I’ll see my mother onscreen. Beats me, sometimes I fancy I was named after Michael Collins.

This uncanny affinity with the Irish might compel me one of these days to go on a séance, lapse into a trance or trick myself into regression, and find out what sort of Irish I was in my previous life. Who knows I could be one of those pot-bellied rascals in a tavern. Or, God forbid, a patchy-furred rat scurrying through the sewers of Dublin after getting a kick from one of those drunkards.There’s also this Irish legend I treasure, wherefrom I draw inspiration in my personal exploration as a poet attempting to define my creative identity.

Once upon a time, the poets of Ireland gathered to see if they could recall together the old epic of the Tain. Of the poem’s entirety, it was known that not one of them remembered. Each of them knew only fragments of it, and so they deemed it their duty to reclaim the epic’s missing parts. In a ritual of remembrance, one of the young poets visited the tomb of the old hero Fergus and invoked his spirit. Finally, Fergus replied to the young poet’s chant, reciting the epic for three days until the young poet remembered it by heart. When the young lad later joined the gathering of poets, he succeeded at last in providing the missing lines, and the epic was finally completed.

In that gathering, I would like to believe, the waiting game of piecing together the epic’s missing parts must have been unbearable without them killing time offering each other a toast of wine until the epic of the Tain sprang forth like a genie out of the bottle.I would like to believe that it was the spirit of fellowship, spurred by the shared grace of the “tagay” that propelled myth and memory to reel on.

The Spirit of Tradition

The young poet’s role in the Irish lore offers a valuable lesson to an apprentice in Cebuano literature like me.For one striving to ground my creative identity in a politically marginalized language, the effort is already fraught with a two-pronged challenge.

My generation of Cebuano poets is not only tasked with every writer’s pursuit in finding an authentic voice; there is also the struggle to stand up on an ancestral ground already swamped with the encroachment of influences from the English and Tagalog languages as well as the inroads of hypertext.

My generation of Cebuano poets is not only tasked with every writer’s pursuit in finding an authentic voice; there is also the struggle to stand up on an ancestral ground already swamped with the encroachment of influences from the English and Tagalog languages as well as the inroads of hypertext.For one still groping my way in a literature that is geographically/culturally off-center, the epic task of reclaiming a creative clearing is a futile effort without a stable foothold on the terra firma of tradition where language is rooted.

My generation can’t do the journey alone. Without the light from the torch of tradition, we can’t go on. Without the voices of ancestry that embodies the spirit of myth and memory, we can never hear the sound of our own.Truly, my creative identity entails a necessity to forge links with the sensibilities of the past, to nourish myself in the spirit of fellowship with the carriers of tradition. Yes, like what the young poet in the Irish legend did in the company of older poets.

Spirit of the Glass

I was 23-years old when I wrote and published my first Cebuano poem (“Balibaran Ko Ikaw Sa Balak”), and that sufficed enough as my password of sorts to a national writers’ congress. Earlier, that poem became a finalist in a poetry writing contest co-sponsored by Cebu’s top newspaper Sun.Star Daily and the Doña Modesta Gaisano Foundation. I was the youngest finalist, and those bottles of beer crowding the tables at the writers’ congress did not leave me inebriated as much as the ecstasy of knowing that the chairperson of the board of judges, Dr. Erlinda K. Alburo, rated my first Cebuano poem with the same grade as the piece of the eventual winner Melito Baclay whose Cebuano works Dr. Resil Mojares deems “world-class.”

Come to think of it, the poem’s last two lines— “… Pagkalapad sa gilapdon/ Sa atong pagpadulong.”— proved to be prophetic in my creative venture. By then, I had also just started to write in earnest English poems (for which I received a fellowship grant to the 1994 National Summer Writers Workshop in Dumagute.) And if not for the impetus of inspiration out of my first Cebuano poem, my excursion into English poetry could have sidetracked my creative foray away from my ancestral terrain.

Indeed, that balak paved the way for Dr. Alburo to invite me as participant/observer to the 1994 National Writers Congress held at the Ecotech Center in Lahug, Cebu City. I would say that the banner trumpeting the theme of the congress— “Toward a National Literature”— marked the crossroads in my aesthetic journey as a Cebuano poet.

At hindsight, I would say that it was in that gathering where I sort of stumbled into the idea of “a writer’s sensibility and responsibility.” No, I did not get that from the papers presented by the country’s literary celebrities. I was too starstruck to care about their speeches; all I really wanted was to gawk at and see that even literary gods can look squirmy at the podium.

If the congress compelled me with an awareness of regional writing as a vital component of national literature, it was because I couldn’t say “no” when two of the Cebuano poets I met earlier at the awarding ceremony of the Cebuano poetry writing contest— Ernesto Lariosa and Pantaleon Auman— asked me to join them in a post-congress powwow with a rowdy bunch of Bisdaks (Bisayang daku or hugely Visayan) over tuba (fermented coco wine) and Tanduay.

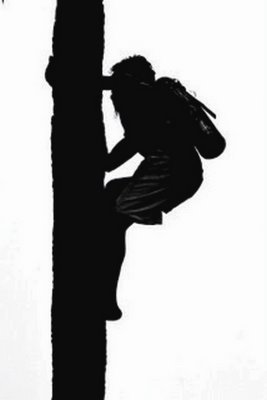

Tasked to be the “tigtagay,” I passed the glass around in awe and amusement as the members of BATHALAD (Bathalan-ong Halad sa Dagang, or Divine Gift of the Quill)— regarded as the largest group of Cebuano writers in the country— reeled me over in a binge of Cebuano songs, impromptu poetic jousts, and tall tales, sousing me up with its undercurrents of folk wisdom and wisecracks.

It was there that I heard Temistokles Adlawan, a recent recipient of the Gawad Balagtas for Cebuano writing given by UMPIL (Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas) who waxed whimsical about his travails as a tricycle driver. With his jaunty spontaneity, with his rambling and rollicking talk, there was no mistaking how the rigors of the road became detours en route to the fury of his poetry. And I owed it to him that I weaned myself from the notion that polishing the creative craft comes only with white-collared high-mindedness. Breezy does it, as far as Tem is concerned about poetics. Only this way would the words bubble over with the piquant spirit of Kondansoy— a native ditty half-remembered from my childhood— dripping from Tem’s tongue: Kondansoy, inom tuba laloy/ Dili ako inom tuba pait aslum…

And why should I care about Li Po romancing the moon at the Yellow River when there’s Pantaleon Auman? With a glass of Tanduay in his hand, Auman was no less ardent: “Bulan, pagkatahum mo/ Sama ka sa maanyag nga bulak nga akong gimahal..” What damsel in the hills of Agsungot wouldn’t swoon with that serenade?

Nevermore would young writers in Cebuano bother about the ravenous fascination on Edgar Allan Poe if they only heard Ernesto Lariosa. A big mole nestling on his upper lip, he hushed us down with the roar of his voice and his gestures so robust. Do you know how Sitio Panadtaran in his hometown in San Fernando got its name? If not, earnestly would Ernie narrate the legend of Juan Diyong, a farmer who spurred the folks into a relentless rampage against invaders in the olden times. With such energy, too, did he keep us wide awake, knocking the bottles off our table at Bayanihan beerhouse while stressing the prerequisite of the 4 S in writing poetry (Sound, Story, and Social Sense). And because the bored waitresses wouldn’t care a whit about the gist of his prize winning essay on Cebuano poetry, his baritone would be tender enough with “Patayng’ Buhi” dedicated to them.

Nevermore would young writers in Cebuano bother about the ravenous fascination on Edgar Allan Poe if they only heard Ernesto Lariosa. A big mole nestling on his upper lip, he hushed us down with the roar of his voice and his gestures so robust. Do you know how Sitio Panadtaran in his hometown in San Fernando got its name? If not, earnestly would Ernie narrate the legend of Juan Diyong, a farmer who spurred the folks into a relentless rampage against invaders in the olden times. With such energy, too, did he keep us wide awake, knocking the bottles off our table at Bayanihan beerhouse while stressing the prerequisite of the 4 S in writing poetry (Sound, Story, and Social Sense). And because the bored waitresses wouldn’t care a whit about the gist of his prize winning essay on Cebuano poetry, his baritone would be tender enough with “Patayng’ Buhi” dedicated to them. It’s been a long while since I served as “tigtagay” in that Bisdak gathering, but the spirit of the glass has lived on from the camaraderie of BATHALAD writers to my generation’s group of Cebuano writers called Tarantula (Januar Yap, Corazon Almerino, Adonis Durado, John Biton, Jeremiah Bondoc, Josua Cabrera, Ronald Villavelez, Greg Fernandez, Delora Sales, Noel Rama, Dindin Villarino, Ulysses Aparece, and yours truly)The way you are now is the way we were, or so Ernie told me as he reckoned the poetry group in late 60s called ALVICALARIVI (after the first two letters in the family name of its members: Melquiadito Allego, Urias Almagro, Romeo Virao, Sozimo Cabunal, Ernesto Lariosa, Edfer Rigodon and Antonio Villavito). It is with a sense of déjà vu, after all, that Ernie and company remember how it was when the pre-war Cebuano literary stalwarts like Marcel Navarra, Laurean Unabia and Diosdado Alesna came to ALVICALARIVI’s drinking table, impressing upon them the sobering task of perpetuating the tradition of Cebuano writing.

It’s been a long while since I served as “tigtagay” in that Bisdak gathering, but the spirit of the glass has lived on from the camaraderie of BATHALAD writers to my generation’s group of Cebuano writers called Tarantula (Januar Yap, Corazon Almerino, Adonis Durado, John Biton, Jeremiah Bondoc, Josua Cabrera, Ronald Villavelez, Greg Fernandez, Delora Sales, Noel Rama, Dindin Villarino, Ulysses Aparece, and yours truly)The way you are now is the way we were, or so Ernie told me as he reckoned the poetry group in late 60s called ALVICALARIVI (after the first two letters in the family name of its members: Melquiadito Allego, Urias Almagro, Romeo Virao, Sozimo Cabunal, Ernesto Lariosa, Edfer Rigodon and Antonio Villavito). It is with a sense of déjà vu, after all, that Ernie and company remember how it was when the pre-war Cebuano literary stalwarts like Marcel Navarra, Laurean Unabia and Diosdado Alesna came to ALVICALARIVI’s drinking table, impressing upon them the sobering task of perpetuating the tradition of Cebuano writing. Replete with discussions (literary and otherwise) and poetry reading, the “tagay” has spawned another round of convocations. At the annual writers’ get-together at the Faigao Memorial Writers Workshop at the Retreat House of the University of San Carlos or inside the erstwhile literary café called Book-o-Bar, or wherever it is that we gather with the brew and verses of our affinities, be it in the honkytonk benches at Planet K (an epithet for Kamagayan, Cebu’s red-light district) or at the demolished Broadway along Osmeña Blvd., the ritual of the “tagay” can’t die. As it never did during the 70s and 80s when ALVICALARIVI evolved and became Bathalad, its members reeling in some vernacular writers from LUDABI (Lubas sa Dagang Bisaya) inside the old State Fair Restaurant or by the watch-repair booth of Bisaya novelist Fidel Magusara and poet Ramon Arong’s candy and cigarette stall at the sidewalk along Colon, the country’s oldest street.

Replete with discussions (literary and otherwise) and poetry reading, the “tagay” has spawned another round of convocations. At the annual writers’ get-together at the Faigao Memorial Writers Workshop at the Retreat House of the University of San Carlos or inside the erstwhile literary café called Book-o-Bar, or wherever it is that we gather with the brew and verses of our affinities, be it in the honkytonk benches at Planet K (an epithet for Kamagayan, Cebu’s red-light district) or at the demolished Broadway along Osmeña Blvd., the ritual of the “tagay” can’t die. As it never did during the 70s and 80s when ALVICALARIVI evolved and became Bathalad, its members reeling in some vernacular writers from LUDABI (Lubas sa Dagang Bisaya) inside the old State Fair Restaurant or by the watch-repair booth of Bisaya novelist Fidel Magusara and poet Ramon Arong’s candy and cigarette stall at the sidewalk along Colon, the country’s oldest street. I would say the drunken reveries of Ernie et al in the company of our new batch of writers in Cebuano has not been for naught. And I know they would drink to this assertion. For instance, in The Poem and the World, a poetry anthology published by the Washington Press of the University of Seattle, more than half of the featured Cebuano poems came from young poets. And I would say that my generation of Cebuano poets have since earned their dues and deserved their seats around the drinking table after winning in the local poetry tilts.

I would say the drunken reveries of Ernie et al in the company of our new batch of writers in Cebuano has not been for naught. And I know they would drink to this assertion. For instance, in The Poem and the World, a poetry anthology published by the Washington Press of the University of Seattle, more than half of the featured Cebuano poems came from young poets. And I would say that my generation of Cebuano poets have since earned their dues and deserved their seats around the drinking table after winning in the local poetry tilts.Sorry if I sound a bit tipsy. But I know the BATHALAD writers and the ancestral voices that passed through them are pleased as punch, seeing we don’t cower at the table of tradition as they pass on the torch, so to speak, to us. Yes, along with the glass.

No comments:

Post a Comment